Phil Rhodes visits the 29th annual New Blades model makers recruitment fair, an event whose continued success demonstrates that not everything needs to be done in 3D.

In something of a reversal of fortunes compared to the situation over the last few decades, London producers are currently struggling to get crew while LA residents have the time to chat with striking writers. It’s cold comfort, to some extent, given the fact that UK residents are living through some truly grim economic conditions in general. Still, thanks to a combination of post-pandemic boom, peak streaming production and a weak currency, the UK is currently experiencing the best time in decades to graduate from a prop and model-making course.

That’s the situation enjoyed by the exhibitors at the New Blades recruitment fair, which has taken place annually for the last twenty-nine years (with the understandable exception of 2020 and 2021). The show took place on June 15 across several of the stages at Holborn Studios in central London, featuring the work of recent graduates from several prominent arts institutions. This year’s crop included students from Arts University Bournemouth, the University of Hertfordshire, Coleg y Cymoedd, the Northern School of Art, and Northbrook College & Wimbledon School of Art.

Given director Christopher Nolan’s well-known keenness to do everything in camera, it’s perhaps no great surprise to find a model of the Endurance, from Interstellar, near the entrance. It was built by Harry Singh as part of a course requiring students to accurately recreate an existing design, though Singh’s work on armour and weapons, featured on his myportfolio profile, is perhaps even more impressive. Next door, Matthew Ericson showed an extremely accomplished model of the armoured personnel carrier from Aliens, built to half the scale of the original studio miniature. A fitting tribute, perhaps, to Aliens as one of the best examples of a movie which did particularly well out of its physical and special effects.

Architecture and the Caspian Sea Monster

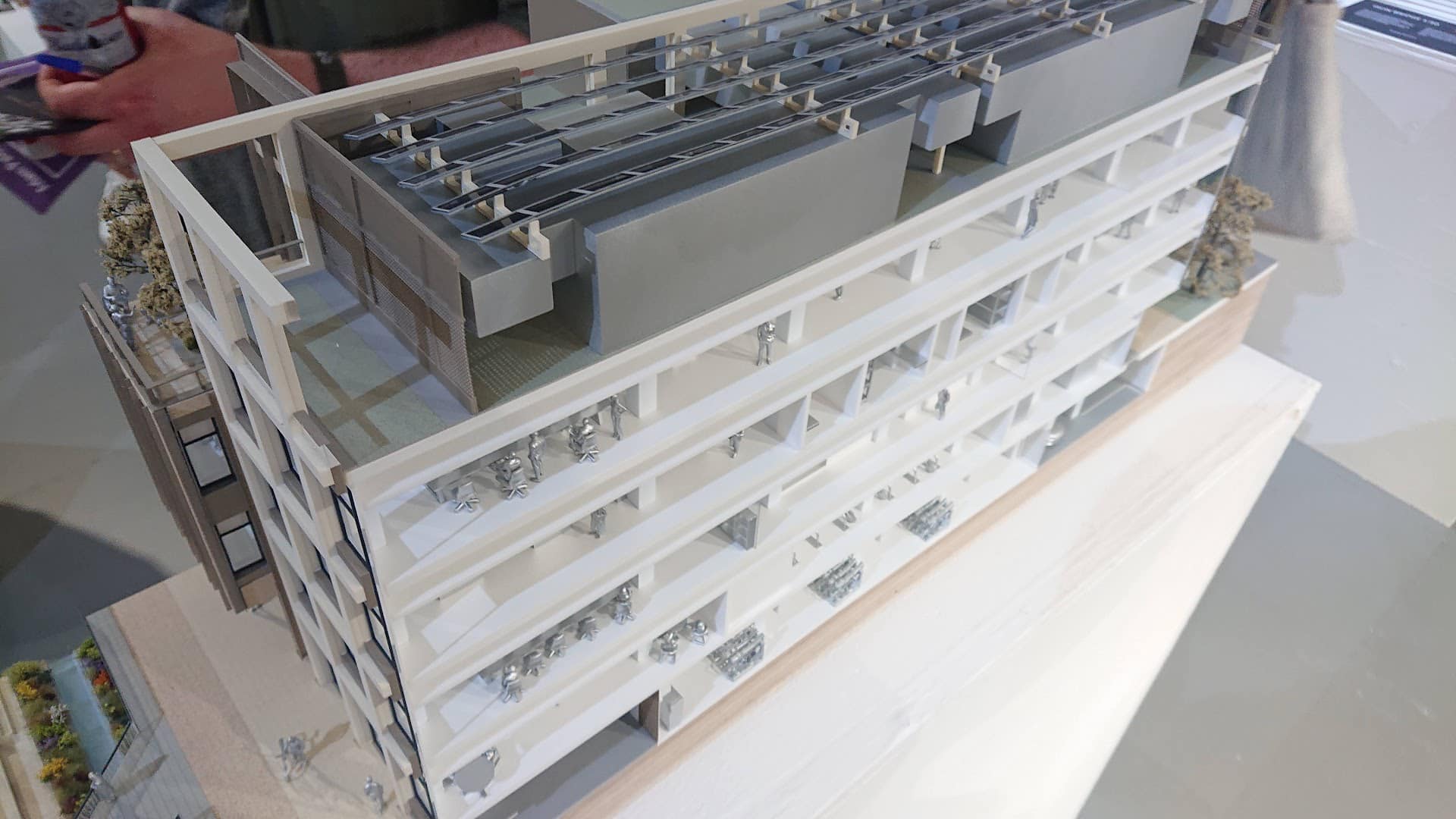

Not everything on show was a film miniature, with some of the graduating students showing detailed architectural models. One showed the recreation of Shakespeare’s Globe theatre, which exists in reality on the south bank of the Thames just a mile or two from the exhibition; others showed real buildings, such as Kyra Byrne’s model of the new Station Row building, and one represented the famous visitor’s centre set from Jurassic Park .Well, it was partially a real building for a few weeks in 1992.

Exhibitor Leo Jeakings, of Arts University Bournemouth, took great pleasure in displaying a scale model of a never-built ekranoplan, a ground-effect vehicle designed to skim just above the surface of water and nicknamed the Caspian Sea Monster (main pic). Featuring twenty (yes, twenty) jet engines and liable to suffer a catastrophic crash if used on rough seas, the design looks like something from a particularly fanciful 1960s science fiction show, though craft like it were built as this video shows. This particularly design wasn’t, although the concept in general turned out to be so deliciously impractical that the idea is perhaps best left as a miniature.

Zak Lewis showed a stop-motion miniature in the style of renowned studio Laika, albeit at half the usual scale. Interchangeable, 3D-printed faces to allow for different expressions are necessarily a fairly new part of the process. Lewis’s decision to make the armature at half size, meanwhile, made for some particularly tiny ball joints and a sparse, delicate construction prominently emblazoned with a do not touch sign.

Your narrator’s psyche is scarred beyond repair by the memory of wobbly sets and unconvincing monsters in 1980s Doctor Who, so he probably didn’t recognise some of the prop recreations from that show. Whether or not a particular exhibit was a recreation or an original work was a perennially entertaining question, though some of the most interesting exhibits were interactive. There was much fun to be had with Kass Harris’s gargoyle glove puppet, which recalled Pratchett and looked endearingly as if it had grown tired of sitting on a rooftop, sieving rainwater through its ears.

There were puddles of blood you could pick up and take home (made from flexible silicone rubber, with a convincingly glossy sheen), rubber guns for light weight in stunt scenes, and a wearable head of the character Roxanne Wolf from the video game Five Nights At Freddy’s: Security Breach. Whether or not that sort of head is strictly animatronic when it’s intended to represent a character which is itself animatronic is at best a philosophical concern, although Christianna Altani’s work was certainly exacting. The mask was reportedly 3D printed, which implies a huge amount of sanding and finishing work, and Altani admitted to having spent quite a few evenings up to her elbows in PLA dust.

Skills in demand

Demand for workers with specific skills naturally fluctuates as jobs come and go, with many effects companies working not only in film and television, but also in live events and theatre. Ordinarily, it would be instinctive to fear for the prospects of young people looking for employment in such a rarefied and specialist field, but 2023 is not a very ordinary year for the British film industry. This year’s event saw representatives of renowned effects houses Artem and Asylum among the potential employers scouting for new people, each reporting demand so high that they were turning work away and desperate for new staff, so there’s probably never been a better time to be a graduate.

Tags: Post & VFX

Comments