replay: Cinematic for the people. Are the new technologies we're seeing in consumer devices like the iPhone 13 (and now 14) going to make some skills redundant. Roland Denning thinks not.

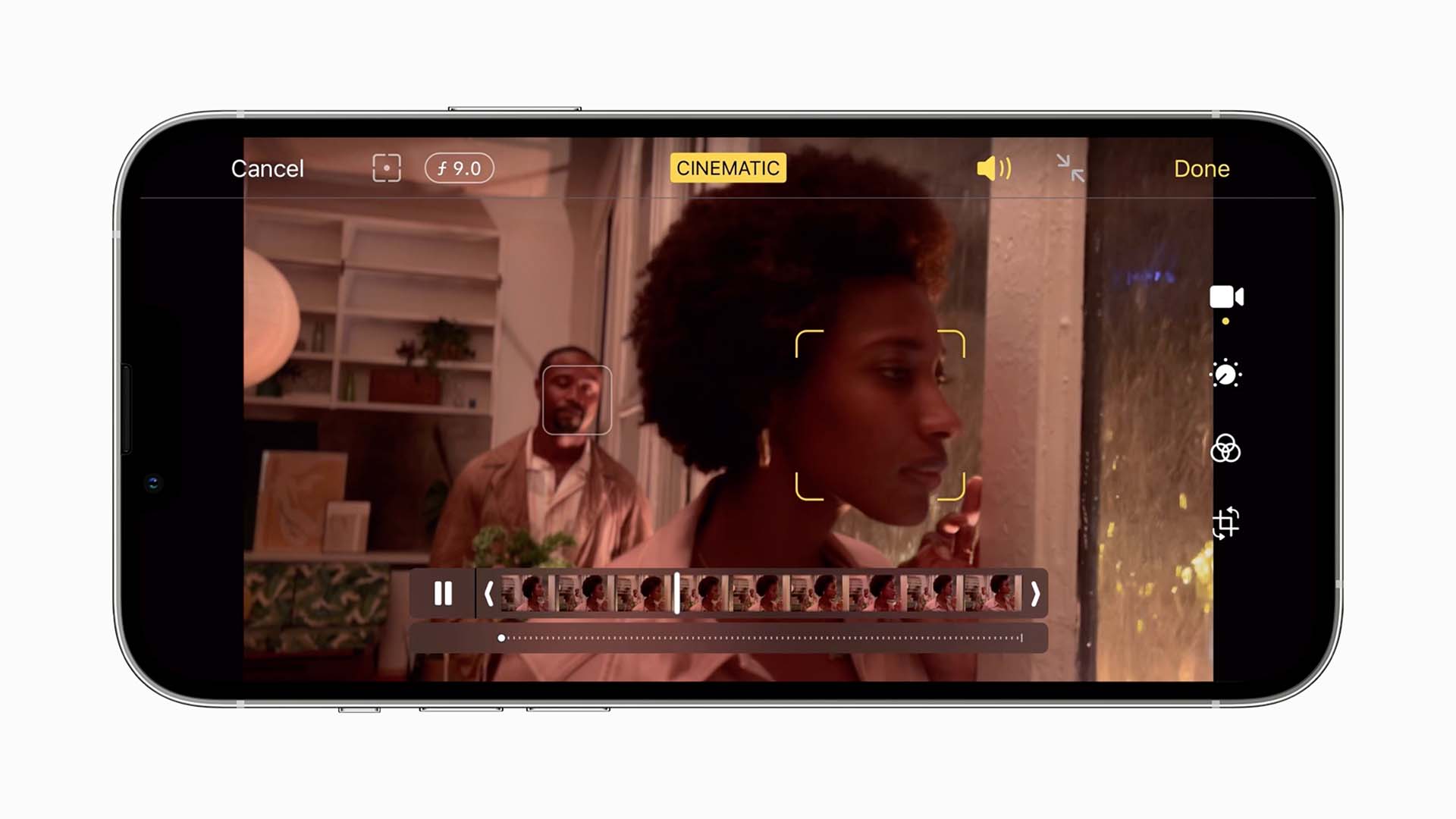

As you probably know by now, the newly released Final Cut Pro 10.6 has a tool labelled ‘cinematic’. Coupled with the ‘cinematic’ mode of the iPhone13, which records depth information, you can now pull focus and adjust your depth of field in post. It’s a very impressive trick. The iPhone 13 will also use AI to rack focus automatically between faces if you let it using (if you want to know more about these features, I recommend this informative video from Ripple Training.)

So what do we make of this? Will commercial movies ever be shot on consumer phones? Or does it just mean that what you shoot on your phone will look more like the movies? And does ‘cinematic’ actually mean anything today?

You can shoot movies on anything

Of course you can shoot movies on an iPhone. It’s been done more than a few times. In fact, you can shoot movies on anything – 16mm, DV, Super8 even Fisher Price toys – and it doesn’t actually make them any less ‘cinematic’. But, in most cases, if you want to make something that resembles a conventional feature, shooting on a phone is just going to make life a lot more difficult.

The tools we use need to match the way humans work together, not the other way round, and, from that perspective, the way feature movies are shot hasn’t changed that much in decades. Yes, the cameras are digital, the focus puller may be a long way away from the lens, we have gimbals and remote heads and drones as well as tracks and jibs, but an operator from the 1940s would find a lot of the action in a 21st century studio surprisingly familiar. Focus pullers are not yet about to become redundant.

Technical advances in consumer devices that have leapt ahead of professional kit. The industry is conservative – but for good reason. Crews like classic kit – big cameras make sense with big crews, and DoPs and operators like classic, beautifully made, robust and consistent lenses. There is no point in arguing that your Chinese or Korean lens gives you pictures almost as good as those made in Leicester or Oberkochen at 20 times the price, because no DoP wants to compromise and no producer wants to take unnecessary risk. Labour, not equipment, is the main cost at the high end, and anything non-standard or unfamiliar that costs a few minutes of shooting time soon becomes a liability.

The innovations in consumer cameras (sophisticated auto focus, stabilisation and, above all, sensor technology) are beginning to trickle up to professional cameras, particularly in the mid-range, but it will be a long time before the high-end fully embraces the potential of computational photography. And by then our definition of what is ‘cinematic’ might have changed substantially.

When does style become a gimmick?

Cinematic is generally defined by what it is not – basically, ‘not like video’ or perhaps ‘not like entertainment TV’. We are encouraged to associate cinematic with shallow depth of field but it not the only game in movie town. It is a current notion of what cinema should look like rather than a defining element. The high-key, hard-lit look or, conversely, gritty, high contrast cinematography is not considered ‘cinematic’ even though the history of classic cinema has plenty examples of both.

If shallow DoF becomes commonplace in phone videos, will it lose its appeal? What once were regarded as flaws in the film medium – grain, flicker, flares, distortion, even lens breathing – have now become features. Overdo it and style becomes gimmick. The more we see rack-focus in iPhone movies, the less it looks like cinema and the more it looks like, well, an iPhone13.

Are phones more advanced than high-end movie cameras?

One thing for sure is that in terms of computational photography, amateur equipment has leapt ahead of professional gear (let us remember we had 4K phones before the Arri Alexa could record in 4k without upscaling). But the huge R & D resources put into mass-produced consumer smartphones cannot be matched in the world of professional kit where cameras are produced in very small quantities. Moreover, pros aren’t craving for neutral lenses whose ‘look’ can be dialled-in in post – although, in principle, it is perfectly feasible – partly because they like the traditional way of working and also because many creative people actually want limitations in the tools they use rather than limitless options (hence, at the very highest end, the appeal of film over digital not for its options but for its limitations – digital can look like anything whereas film, well, looks and feels like film).

Amateurs want equipment that gives them ‘professional results’ as easily as possible, but professionals want maximum control, and their end result is a constantly moving target. So focus pullers are not about to become redundant, and legendary lens-makers will still benefit from the production boom. For the moment.

Looked at another way, we are in a transitional phase. Increasingly, the movies we seen our screens will be partly or largely computer generated, and perhaps we should stop regarding the feature film as the form we all aspire to. The sort of technology that the iPhone uses to imitate traditional movie making will just be part of the vast gamut of digital production technologies, and feature movies and the high-end drama a tiny minority of the moving images that occupy our screens. GarageBand has not made symphony orchestras or grand pianos redundant, but traditional analogue methods are increasingly luxury items for the very few. We will still need focus pullers, just as we will still need tuners for our Bechsteins and Steinways, but pulling focus in post will be as commonplace as adjusting the reverb on your recording.

Tags: Opinion

Comments