The Revenant meets Gravity was how George Clooney pitched his latest film to cinematographer Martin Ruhe ASC. We interviewed him to find out just what went into the making of the film, and the technology used.

The Midnight Sky, which Clooney directs and stars in, lands on Netflix this month. It’s a post-apocalyptic tale of survival about Clooney’s ageing scientist Augustine racing to stop Mission Specialist Sullivan (Felicity Jones) and her astronaut colleagues onboard the Aether from returning home to a mysterious global catastrophe.

It’s a human drama more than a sci-fi action film in which both principal characters have made sacrifices. Sully for instance left a daughter behind on earth. So when Mission Control falls inexplicably silent, she and her crew mates are forced to wonder if they will ever get home.

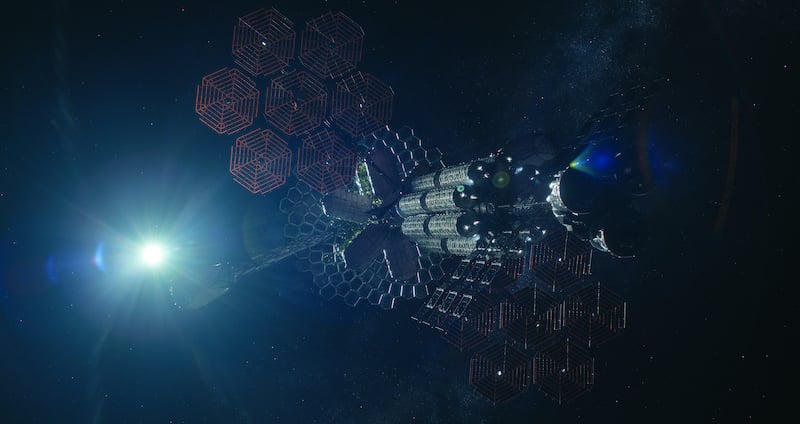

“We watched a lot of space films in research and in particular wanted the design of the spaceship in our movie to be different,” says the German DP who shot previous Clooney-directed projects including The American and Catch 22. “With production designer Jim Bissell (E.T, Jumanji) we asked ourselves what a spaceship in 2060 would look like. We decided it’s a design that could be printed in outer space by 3D printers.

“We also constructed the spaceship to have some areas of gravity and no gravity in others and there are also some sequences of a spacewalk. My thought was to have a floating camera so as not to lose the sense of gravity but also to feel weightless. We shot these sequences using a lot of Steadicam with a constant movement and rotations of the camera so you feel like you could be upside down.”

The Midnight Sky. Image: Netflix.

The film is also set in the Arctic for which the crew endured a gruelling shoot in Iceland.

“We shot on a glacier with limited access and minimal crew in really rough and stormy conditions,” he says. “We were there for a month, two weeks of which we couldn’t get to base camp. We stayed in hotels and drove 45 minutes along a dirt road to the base camp and then took snow mobiles and jeeps to get onto the glacier. We used a Super Techno on wheels especially constructed by ARRI for this terrain, and shot drone footage.

“George would spray water into his beard and it would freeze in seconds so it looked like he’d been walking through the snow for hours.

“Sometimes we had to wrap up all the cameras. It would take 15 minutes to change a lens. Snow would get everywhere. One day we found our containers had blown away.

“But the light was beautiful. The nature amazing and the sheer scope of the sky and landscape just blows your mind. It’s just not easy to work in.”

The Midnight Sky. Image: Netflix.

To capture what is a very intimate story set against the extraordinary scope of space –both terrestrial and galactic – Ruhe chose the ARRI Alexa 65 format with detuned DNA lenses shooting full sensor 6K and finishing in 4K. This camera was augmented with Alexa Mini LFs in the confined space of the spaceship.

“Shooting 65 feels more intimate even though it’s larger format,” he says. “You end up going closer with wider lenses and a shorter field of view. I love the detail you get in the faces and how you can single out characters from the background.

He adds, “We ended up not shoot so much at night because the scenes involved a 7-year old girl and it’s not possible to do night exteriors at that temperature with a child actor.”

The Midnight Sky Previz. Image: Netflix.

While there is VFX work from ILM and Framestore, much of the film is shot in camera. The spaceship interiors were lined with hidden LED strips which the DP could interactively control, variously switching between blue tinged control panels contrasted with red and warmer tones in the living areas. Likewise, Ruhe mixes in warmer tones in the arctic scenes, such as when the sun rises, so it’s not all bleak, cold and blue.

For a hologram displaying the movement of Jupiter he shot the actors with a series of china balls for VFX to replace with an animated model in post.

“A lot of the space sequences were designed with a virtual camera,” he explains. “I would go into a meeting room with the virtual camera and an iPad and I’d say ‘give me a 58mm’ or ‘I want to be at this scale’ and I could immediately see an animated render of the spaceship interior and exterior and models of our actors. This pre-vizualisation would inform production design or stunts for the wirework or for myself and George it helped us judge the timing and blocking of the scene.

“Rather than being led by the limits of technology we were using technology as a tool to help craft the scene.”

Principal photography began in mid-October 2019 and ended just before lockdown in February this year. Ruhe and Clooney completed the grade remotely using Sohonet Clearview viewed on iPads before Ruhe returned to London for grading sessions with Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3. The colorist was in LA, Ruhe was in London and Clooney was viewing the realtime session at another screening venue in LA.

LED screens of the type used extensively on The Mandalorian used to light interior shots of the Arctic set interiors which were shot at Shepperton.

“We used plates shot in Iceland as background to the windows in these scenes,” Ruhe says. “Since the views and reflections are real it helps the actors if they can see a landscape or a night sky.”

Comments