A couple of weeks ago, Sony put back the launch of a new camera citing chip availability concerns. The idea of one of the world’s biggest electronics companies postponing something like that at a couple of days’ notice is fairly extraordinary. What’s going on with the global chip shortage?

Well, as anyone who’s tried to buy a graphics card in the last few months will have realised, there’s a bit of a shortage of microchips on planet Earth. That’s for a few reasons, not all of them directly related to the pandemic, and not all of them easy to justify in terms of what we might call reasonable business processes. They’re less likely to affect big-ticket items like high-end cinema cameras, whose components only make up a fairly modest proportion of their cost. Things like Sony’s new vlogging camera, though, which would usually be a large volume seller and a bread-and-butter product to a big company, are more cost controlled and made in larger numbers, and so more exposed to price fluctuations in the parts used to make them.

The influence of the pandemic on the demand for computer equipment, with vastly more people working from home than usual, isn’t hard to understand. One of the less predictable outcomes of it was that desktop computers – a market long in decline – perked up considerably. While it’s certainly possible for most people to run the classic combination of web, word and email on a laptop, tablet or even an ambitious phone in 2021, doing that all day every day is a lot less provocative of eyestrain on a real computer. And while all that demand was happening, many people were staying at home in order to minimise exposure to the virus, and so a lot of chips didn’t get made.

So far, so obvious.

The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company

But it isn’t quite that simple. At the same time, a serious water shortage occurred in Taiwan, affecting the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, TSMC, one of the world’s most capable chip manufacturers. TSMC are the people who make the M1 processor for Apple, Nvidia parts and at least some of AMD’s output of both CPUs and GPUs. The lingering effects of Trump’s trade war against China has made it difficult for anybody with US connections to buy Chinese semiconductors, regardless whether they can be made or not. Going outside China to TSMC or Samsung to solve the problem works, but at some point those companies have a capacity limit.

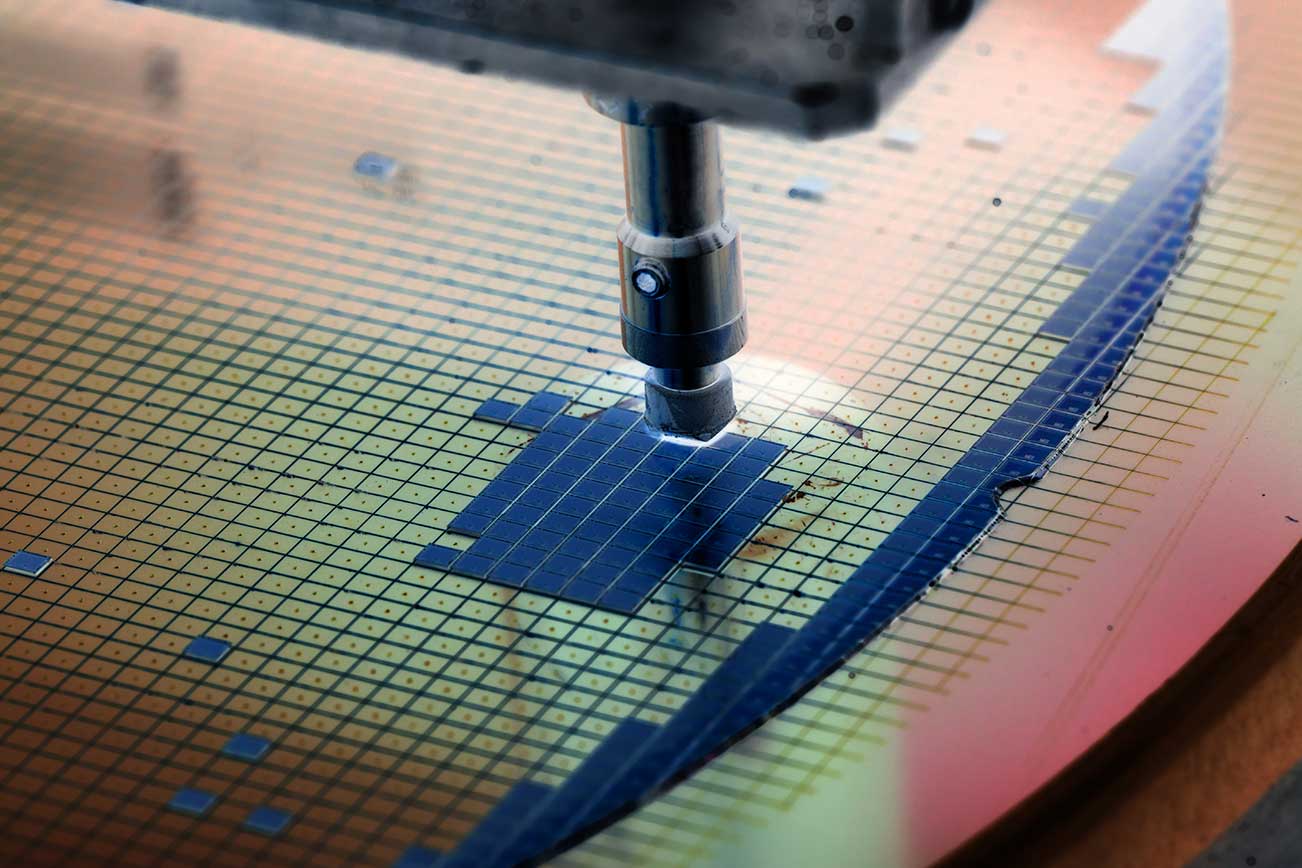

Worse, the high-end manufacturing facilities in Taiwan, and in a couple of other places around the world, are only part of the story. When we talk about microchips on RedShark, we’re often talking about state of the art imaging sensors, high performance microprocessors, FPGAs and the latest graphics cards. These are devices at the very zenith of what’s currently possible; things made to the limits of what humanity knows how to create. The vast majority of microchip manufacturing, by sheer count of parts, isn’t anything like that. It’s the microcontroller that runs your washing machine or microwave, or controls the antilock brakes and traction control in your car. They’re not hugely high performance, but making them is a high technology process and shortages create major problems nonetheless. Ford reportedly parked up a huge number of almost-finished cars, waiting for parts to complete them.

A silicon wafer die during manufacture. Image: Shutterstock.

GPUs and cryptocurrency

Finally, and specifically in the context of GPUs, the price graph follows the price of the Ethereum cryptocurrency with stunning accuracy, from a bump around the end of 2017, all the way up to a ludicrous peak of perhaps four times their launch price in mid-2021 – and it’s still rising. Changes in Chinese law may change the usefulness of cryptocurrency mining, and there are reports of used GPUs flooding the market, at least in places local to the datacentres where they were once used. It remains a vexed question whether or not it’s a good idea to buy a graphics card that may have been run at a high performance level for months on end. Still, while it’s hard to object to staggeringly wasteful cryptocurrencies being taken down a peg, it hasn’t yet had much of an effect on the street price of GPUs.

So that’s why this article is being written on a workstation that’s increasingly out of date; replacing it without taking a huge hit on price may not be possible for more than a year. Worse, this situation coincides with a problem at Intel that’s been at least a few years in the making, significantly predating the pandemic. Why can TSMC make processors on a 5nm process while Intel is still to ship 10nm? Well, only Intel can really answer that question, although the company did announce that in 2020 it expected to spend over $14 billion buying back its own shares in order to maintain its stock price. At the same time it had spent less than $11 billion in total capital outlay, which would include money spent on improving its foundries at a time when its smaller process sizes were already late.

Priorities, people.

Unfortunately, improving the manufacturing facilities takes longer than one financial quarter to pay back. Wall Street is less patient. Perhaps by the time things calm down a little, the state of play at Intel might be a bit clearer. Perhaps also, some big workstation-class ARM CPUs might have been offered by both Apple and, crucially, others, though they still have to be manufactured somewhere. Regardless, if that happens, we might.

Tags: Technology Business Editor Featured CPUs

Comments