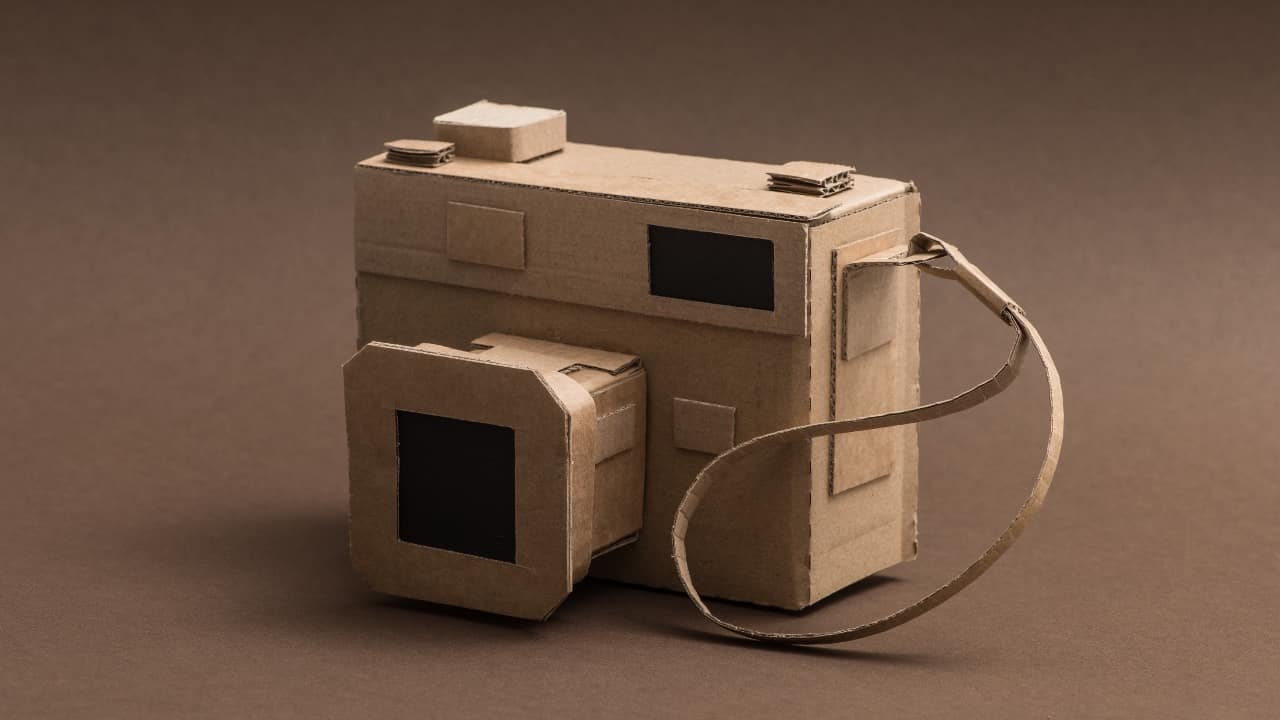

Roland Denning on how digital has created a much more level playing field when it comes to buying kit, and how Asian manufacturers are extending that democratisation into whole new areas.

There was a kit review in RedShark News a month or so ago, which evoked a couple of rather dismissive comments. The commentators reckoned such inexpensive gear was strictly for the lower echelons of vloggers and YouTubers rather than actual filmmakers. But who or what is an actual filmmaker?

We are all engaged in film and video production but let us not pretend we are all working in the same sector. You buy the gear that works for you, but please don’t fall into the belief that those working in the sector below you are somehow not doing it right.

Those working at the high-end would be foolish not to use recognised high-end gear, whereas those working at the other end would be foolish to pay more than they have to. Unsurprisingly, it all comes down to money.

It's the crew not the kit

I see our world roughly falling into three sectors:

The high end of features, TV drama and commercials. We know the kit. The cameras are ARRI, Sony Venice, or maybe RED. The lenses and microphones are made in Europe or possibly the USA. But it’s not really the gear that makes great pictures. High-end gear allows very experienced and talented crew to make those great pictures. High-end gear fits into the working practices of a professional crew and the post-production chain. The kit has to be very robust, very consistent, familiar, and produce totally predictable results; making a lens mechanically robust and precise is not a trivial or inexpensive task. Despite the price of premium gear, it is the crew that cost the money and any delay, whether it is to do with equipment failure or because something doesn’t quite work the way expected, will cost money. Cheaper kit would be a false economy.

Below that is the TV documentary sector where, again, standard equipment and engineering standards rule, but perhaps not so much as they once did. While traditional shoulder-mount ENG cameras are still around, mirrorless cameras and smaller camcorders are taking over for news and low-end docs. It’s an area that, certainly in the UK, Sony has dominated, followed closely by Canon. Independent broadcast producers also want to work with common standards and kit: if a producer specifies S-Log 3, that’s going to determine the brand of camera you can use.

Then, there is what we could call the third sector. It is everything else, and it is huge and, unlike the above sectors, kit tends to be owned rather than hired. I suspect many, maybe most, of our readers are part of it. It is the people making work to show on screens in exhibitions, museums and theatres. Corporate, training and PR videos. Travel docs. Low-budget music promos. Artists doing weird stuff. Wedding videos. Aspiring indie enthusiasts making pioneering dramas and docs that no one else would make. And vloggers, who perhaps are in a category of their own with dedicated gear and their own rules.

This sector is largely composed of small teams who own their own gear and control the whole production process. As they don’t have to fit into anybody else’s concept of standard or approved equipment, they can save huge sums of money by buying mid-range kit. Your kit may be a little fragile; it may have foibles, but you know them, and you can handle it. And you can operate with much more autonomy than those who are a small cog in a large machine.

There are many bits of mid-priced kit that hire companies stay well clear of because it is perceived they cannot stand up to the rigours of constant use by different people or because it is not a brand familiar to producers. They offer great possibilities for those on low budgets and much better results than those in the sectors above would willing admit. And if you look at the latest products from companies like Røde and BlackMagic, this is where the innovations are happening.

The levelling effect of digital

In the analogue days, 8mm film was never going to match 16mm, let alone 35mm. Broadcast standard video equipment like BetaSP inevitably produced much better pictures than could be achieved on industrial and consumer formats.

All that changed with digital. MiniDV and its variations was the first video format targeted at both professionals and amateurs. There was still a big difference in camera quality until the DSLR/mirrorless revolution meant a low-cost camera with a mass-produced sensor could potentially create an image for the cinema screen as good as that from cameras costing thirty times more. Digital audio has meant high quality recordings with negligible noise levels or distortion are available to anyone.

Just to be clear – there is a lot of very low-cost junk out there, which everyone should stay well away from. Nor am I claiming that very expensive equipment does not produce finer results than moderately priced kit, just that the latter, in the right circumstances, can do the job just fine.

The key thing is that if you have a great story and your camera, lights and microphones are in the right place, no one is going to say – that would have been a great film if only they had used an ARRI not a Blackmagic, or a Cooke not a Sigma, or a Shoeps not a Røde.

But we are beginning to see change here. Asian manufacturers are upping their game with much better-built products at higher cost but still much lower than the established European brands. Another interesting development in the last decade is small ‘artisan’ lens makers, mostly in China, using classic but simple lens designs aimed at the indie film sector. They lack the advanced proprietary technology of the big three Japanese manufacturers – like sophisticated autofocus and stabilisation – and usually come with their own set of quirks, but that doesn’t seem to be an issue in this particular market which, interestingly, seems to have been defined by users rather than industry.

We should celebrate the fact that it is cheaper than ever to put great pictures on the screen. There will always be a high-end, not because extravagance is a movie tradition (although it sort of is), but because ‘production values’, the sort of looks you can only get when a lot of talent and a lot of time go into a production, will always be sought after. And for everyone else, there’s never been a better time to build up your own kit.

Tags: Production

Comments