I suspect I've always been an Abba fan, but I didn't admit it until recently. I didn't realise how clever the music was until I sat down and consciously analysed it. It's multifaceted. It's complicated.

And it's just brilliant pop music.

So when I heard about the ABBA Voyage concert, a new production that is actually not real but a virtual representation of the 70s supergroup, I wondered what it would be like. Despite the popular press almost universally saying that it will consist of avatars which are holograms, I think I knew from an early stage that it wouldn't and couldn't be based on holography. The technology simply doesn't exist yet, and I'm sure I'd have heard of it if it did.

So it raised huge questions about how it could be done. I've since discovered that it doesn't rely on any kind of three-dimensional technology at all. Instead, the stage is taken up entirely with a gigantic and resolutely two-dimensional LED screen with a massive resolution. To the sides were two zoomed-in views of ABBA members, with a virtual camera able to move all around the characters. I'm not sure whether this was part of the main screen or two additional ones, but their purpose, I'm sure, was to act as a distraction from the fixed-distance, 2D performance on the main "stage".

You might think that a two-dimensional performance on a screen would be terribly restrictive in a supposedly live show, but it doesn't have to be, and the show's reviews have borne this out.

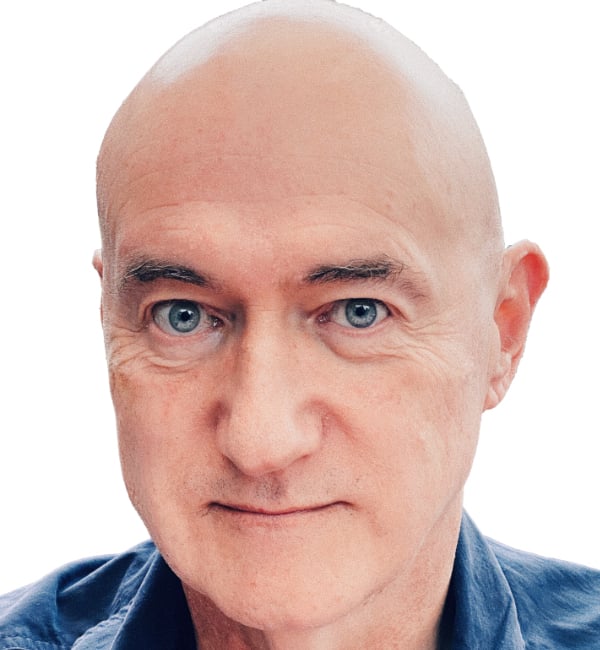

The photoreal ABBA Voyage avatars. Image: ABBA.

Are holograms necessary?

For a start, you have to ask why Holograms would be necessary or even desirable in a show where the audience will be in front of the avatars. There's no way for the audience to look round the back or even particularly to the side of the "performers", so there's no point in making them genuinely three-dimensional. In fact, even if the concert had been designed primarily to take place in the metaverse, there would still be no practical or artistic reason to allow those watching in full immersive 3-D virtual reality to go round to the back of the performers.

With this decision in place, The production process becomes massively simpler. But it still leaves the problem of having a two-dimensional performance pretending to be three-dimensional. This, to me, is where the cleverest stuff actually starts.

With the creative process focused on making the best-looking two-dimensional images, there was time to consider the performance in its entire context. And that context is that of a theatre with real humans and actual human responses to what is apparently on the stage.

I would guess that a fundamental priority would be to smooth out the boundary between the real space, containing the audience - and the live band - and the two-dimensional screen on the stage. Don't forget that the screen is the only thing on the stage! So it's a pretty distinct and perhaps brutal boundary to have to ameliorate.

And the way they've done it is both simple and incredibly clever at the same time.

ABBA Voyage concert.

How they did it

The technique is to mirror what's on the screen with what's happening in the auditorium, mainly through the clever use of lights. I haven't yet been to any of the concerts, and I absolutely will as soon as I can. But what I've seen and heard from the very limited clips and presumably unauthorised mobile phone footage leaked out is that the spectacular lighting above and behind the actors, which is obviously depicted on the giant screen, is replicated with real matching lights in the actual auditorium.

The whole process is incredibly well synchronised, as it has to be. The auditorium lights, which are fully computerised in every sense, run in synchrony with what is depicted on the screen. The effect is a total and convincing continuation of the space shown on the screen within the physical area of the theatre itself. For example, if the lights on the screen are shining behind the actors on the stage and then raise to point the beams of light toward the audience, the physical lights in the auditorium will do precisely the same thing, at exactly the same time. Clearly, while the screen action was created first, at the planning stage, the entire production, both on-screen and in the physical space, would have been considered at exactly the same time.

Other aspects of the production add to the illusion. One of the smartest moves was to use a live band with, I think, 12 musicians and backing singers. The ABBA avatars sing to isolated vocal tracks taken from what I presume is an original recording. I'm assuming that even though, based on the Voyage album, the original members of ABBA are still in fine voice, they would not have been able to sing at the pitch or intensity of the original recordings. If the entire original mix had been used, it would have lacked the "live" feeling. Having a live band in the production very cleverly alleviates this problem.

ABBA Voyage. Image: ABBA.

A new kind of concert

Many commentators have said that the ABBA concert is the start of a new kind of live entertainment where all sorts of artists, dead and alive, appear as they did at their career peaks on stages in front of live audiences. I think this is very likely, but remember that approximately 1000 people worked on this production for several years. Whatever else it is, it's not cheap.

But I have no doubt that this methodology will make this type of content commonplace. And in the process of that happening, we will become more efficient at producing these concerts, mainly because the tools will improve, and artificial intelligence will be at the core of these productions.

There's nothing particularly new about making an artificial production seem real by adding distortion or camera shake or even film grain and discolouration. The original BBC series "Walking with Dinosaurs" looks pretty clunky from today's perspective, but you have to admire its ambition. The state of the art was not particularly advanced then, and the production company cleverly used camera shake to smooth over the barrier we discussed earlier between the digital recreation and the viewer.

What I think we can also conclude from this is that resolution in terms of pixel density is not the most critical factor. What matters most is the end result: the combination of resolution accuracy and the environment or context. When you think about it, it's only quite rarely that the actual resolution of an image or film is starkly visible to us for our analysis or approval.

And as we move into an era where AI has an increasing role in productions, it's not the pixel resolution of images that matters. Instead, it is the "intelligibility "of the information in those images, and it's about the quality of the concepts depicted in the production. So we are perhaps, witnessing the start of an era where quality is no longer assessed as a technical parameter like pixels but instead as a cognitive measure, and ultimately an aesthetic one.

Comments