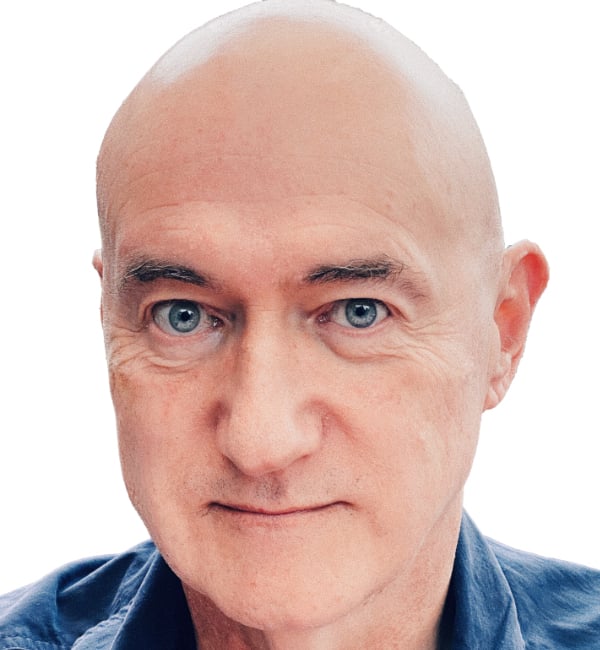

David Shapton dons a pair of Sony MDR-MV1 open-back reference monitor headphones and is seriously impressed by their audio quality.

Sony's MDR-MV1 headphones might confuse followers of modern headphone trends. There's no Bluetooth, noise cancellation, helpful voice prompt, or internal batteries to charge. Instead of a USB port (or Apple Lightning connection) the only chord tethering these headphones is an audio one. These phones are strictly analogue, and all the better for it.

The headphones are targeted not at consumers but at audiophiles and studio professionals. As such, they're keenly reasonably priced. What makes them really stand out is that they are open backed, a feature that has a massive consequence for the sound.

Most over-ear headphones are sealed inside a small chamber containing audio drivers. This can flatter the sound - basses sound bassier, for example - but can also degrade it. Internal reflections and resonances build up in the space between the ear and the headphone driver, making obtaining natural sound harder. There is some sound leakage - proof that they are truly open-backed, but it’s only obtrusive in a quiet room. They don’t draw attention to themselves, and most people wouldn’t notice.

But do people really want a neutral sound? Consumers probably don't. They want to hear as much energy and sparkle in their music as possible. They don't want "flat"; they want "flattering".

But just as we wish there were more truth in politics, truth in audio is a necessity for audio professionals. If you're an audio content creator, you need to hear what's really there. Just ask a professional video colourist. Would they want to grade critical footage on a monitor with "in-store demo mode" turned on? Of course not.

Please don't think that "flat" as in "accurate" also means "flat" as in "boring". Quite the opposite is true. With accurate-sounding headphones, you hear more detail, more nuance, and more of the original artistic intent than if everything is massaged to within an inch of its life. That's not to say Bluetooth headphones are rubbish: Sony makes some brilliant ones, but it's horses for courses, and professionals need the simplest, kindest path between the music and their ears.

Sound and build

The MDR MV1s are very lightweight at only 223g. They’re made from aluminium, which gives them heft without excessive mass. Compared to Apple's Airpods Max (admittedly about the heaviest phones on the consumer market), they feel almost weightless. But, somehow, they also feel pretty robust, and they need to be to withstand the rigours of professional use.

There are some thoughtful touches. The detachable audio cable has a locking mechanism at the headphone end and a converter for the two traditional headphone jack sizes. The phones themselves are quite deep, but about half of that is the soft Alcantara ear cushions. They are incredibly comfortable, and I find myself simply forgetting to take them off, even when I'm not using them.

And so, to the sound. You'll know what to expect if you've read the previous paragraphs. Except that you quite probably won't. The fact is that these headphones sound great, but in a different way, one that you might not be accustomed to.

The sound is understated - in a good way. There is a very bearable lightness to its being (with apologies for the obscure film title reference. This understatement lets you hear the "character" even in bass sounds (often lost in room resonances). If you listen to the Carpenters' A Song For You, you can hear the character in the reverb plate and the exact nature of its decay. The sound is intimate, without any overbearing presence. I had never noticed that level of detail before.

Pushing the Sony MDR-MV1s

Joe Jackson's Be My Number Two surprised me with its dynamic range. Eighty per cent of the track's duration is voice and solo piano, but it finishes with full and loud instrumentation. To my surprise, the piano sounded like it had been through a degree of (dynamic range) compression. This wasn't imposed by the headphones but revealed by them. It is on the original recording; I have never noticed it before.

Stevie Wonder's Contusion (from Songs In The Key Of Life) is a tricky track packed with dense rapid-fire instrumentation and an edgy bass guitar. But each element was clearly audible, and you could appreciate the remarkable skills that went into playing this challenging piece all those years ago. A sign of real clarity is being able to "hear" the studio in old recordings. That's a good thing. You hear the constraints of the recording techniques and every subtle microscopic clue about the time and the place. It's like time travel: an audible hologram. You can only hear this with truly accurate loudspeakers or headphones.

The headphones easily handled Original Nuttah by UK Apache/shy FX, reproducing the deep and prominent sine-wave bass without clouding the rest of the detail. They rendered Bernard Haitink's recording of Mahler's second symphony's final movement - including the tumultuous final crescendo - convincingly and without audible signs of stress. The LSO's version of Aaron Copeland's Fanfare For The Common Man was energetically uplifting, and the same orchestra's version of his Appellation Spring seemed to hover in space, with a much wider soundstage than you would expect. One thing that stands out is that you hear the acoustic texture of stringed instruments; the bow scraping on the strings and the gritty, penetrating strength of a string ensemble; these are nuances that are often lost in the “generic”, stereotypical reproduction of most consumer devices.

Airy and spacious

I tried the headphones with the dedicated headphone-out of my ASM Hydrasynth, a complex digital synthesiser that can push audio devices past their limits. Exactly as you’d want, the phones shrugged off even the most abusive sounds and sounded good at the same time. It sounded infinitely better though the phones than though my monitor speakers, chiefly due to the absence of room resonances, which typically destroy any nuances from a synth, especially in the bass region.

The MDR-MV1s are airy and spacious, with a wide stereo image that sometimes seems to extend way behind the physical limits of your head. They prove that accurate headphones with a flat frequency response can, at the same time, be incredibly satisfying. I'd forgotten the elegant simplicity of unpowered, unprocessed, absolutely non-digital headphones, and I highly recommend these.

Street price varies but is in the region of $400. Find out more from Sony here.

Tags: Audio Adobe Audio

Comments