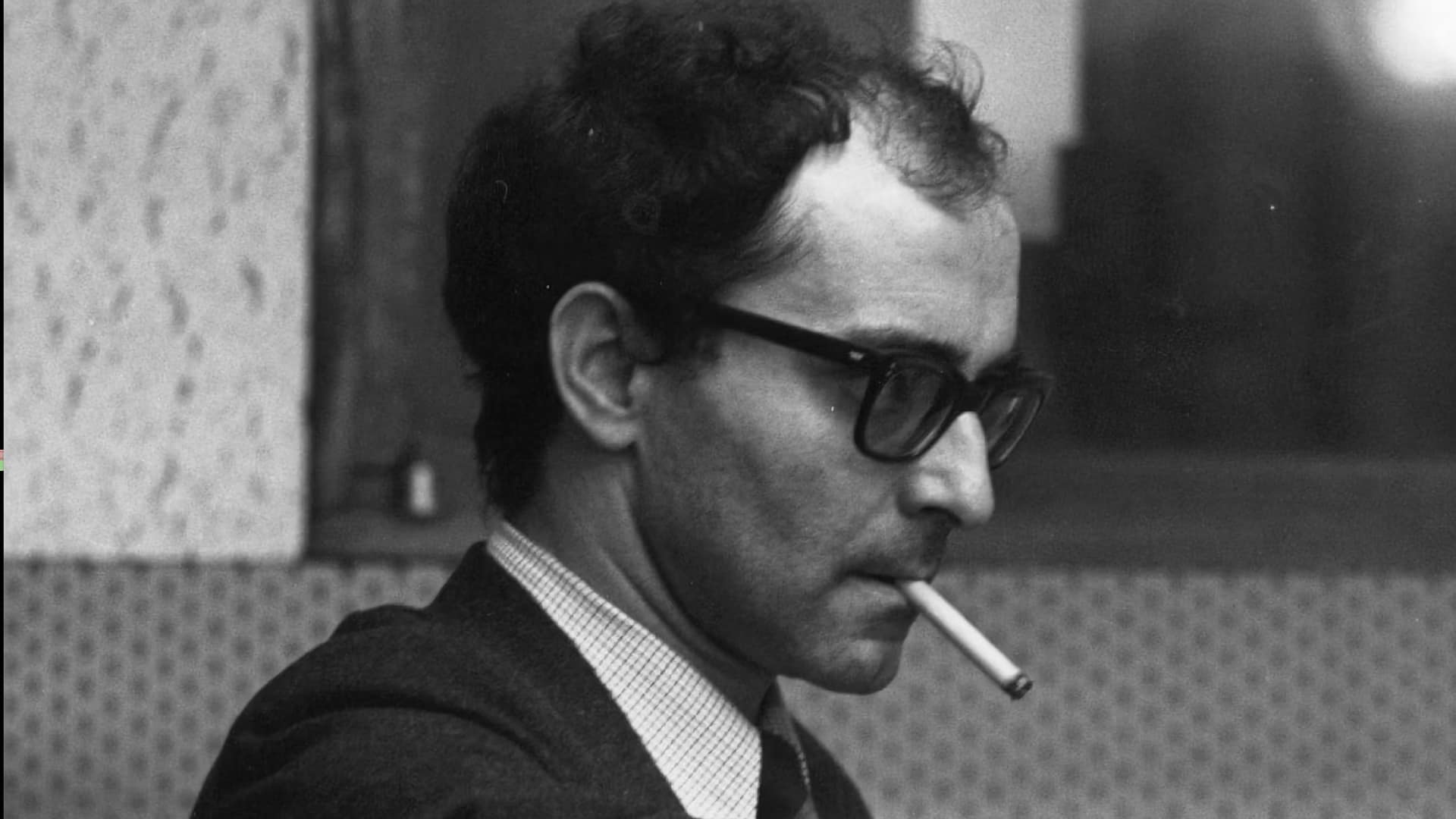

God is dead. Or, to be more precise, Jean-Luc Godard, the enfant terrible of the nouvelle vague and one of the greatest film directors of all time, has passed away at the age of 91.

I am an unashamed Godard fan. To my mind he was the most innovative, dazzling and simply the most fun of all the new wave directors. He was also the most infuriating, contradictory, pretentious and obscure.

A former film critic for Cahiers Du Cinema, he hit the screens with his first feature Breathless (A Bout De Souffle) in 1960. Obsessed with American cinema but also determined to rip it apart, it’s the story of a charismatic criminal (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and his American girlfriend (Jean Seberg) which, amazingly, is as fresh and stylish today as it was 60 years ago.

It takes liberties with cinema conventions (jump cuts, continuity breaks, addresses to camera) that echo the unruliness of the main character. Shot by Raoul Coutard mostly by available light with a handheld Cameflex camera on spliced-together rolls of Ilford HPS 35mm stills stock (there wasn’t a fast enough movie stock available at the time), the film was made fast and cheaply. Clearly Godard and Coutard were enjoying themselves enormously – it is a film about breaking the rules. It was a huge success.

Through to 1967 Godard made 14 more astonishingly innovative and successful films, the best known of which are perhaps Band à Part, Le Mépris (Contempt) with Brigitte Bardot and Pierrot Le Fou. Film festivals of this period expected not just one but two or three new and totally different Godard films to appear. Perhaps my favourite of this period is Alphaville, a romantic comic-strip vision of the future shot documentary style without sets or special effects in contemporary Paris.

This period ends with Week-End, a rather wonderful film about a couple secretly trying to murder each other which ends in a never-ending traffic jam. Godard’s films seem very modern in their obsession with the landscape of media – advertising hoardings, TV ads, posters, slogans – that surround us, and are treated with equal respect to quotes from poets, philosophers and artists.

From 1968 onwards, things became a little weird. Godard became, ostensibly, a Maoist and teamed up with Jean-Pierre Gorin to form the Dziga Vertov group. Although very involved in the protests of May ’68, Godard’s politics were never straight-forward, and one could say he was more attracted to revolutionary style rather than revolutionary politics. Some of the 15 or so films of this period are, frankly, unwatchable, but they include British Sounds (financed but never screened by London Weekend Television), One Plus One (set around the Rolling Stones recording Sympathy For The Devil) and Tout Va Bien starring Jane Fonda, a film about a factory strike which is also about the politics of making a movie.

Godard carried on making films up until 2018, increasingly working on video from the 90s onwards. He never returned to the commercial success he had in the 60s, increasingly making often impenetrable reflections on cinema, art and the meaning of life. In 2014 he surprised everyone by making Goodbye To Language, a feature length movie in 3D using Canon 5Ds, which is both as likeable and opaque as anything he has done. But even in his most impervious meditations there are sequences which spring out at you which you know could not have been made by any other filmmaker.

Here is a short film (14 minutes) I made about Godard for the English language service of the Latin American broadcaster teleSUR, featuring Godard expert Michael Witt, which explores this remarkable filmmaker further.

Let’s end with one of Godard’s gnomic quotes:

“What is your greatest ambition in life?”

“To become immortal... and then die.”

Jean-Luc – I think you’ve achieved your ambition!

Tags: Production

Comments