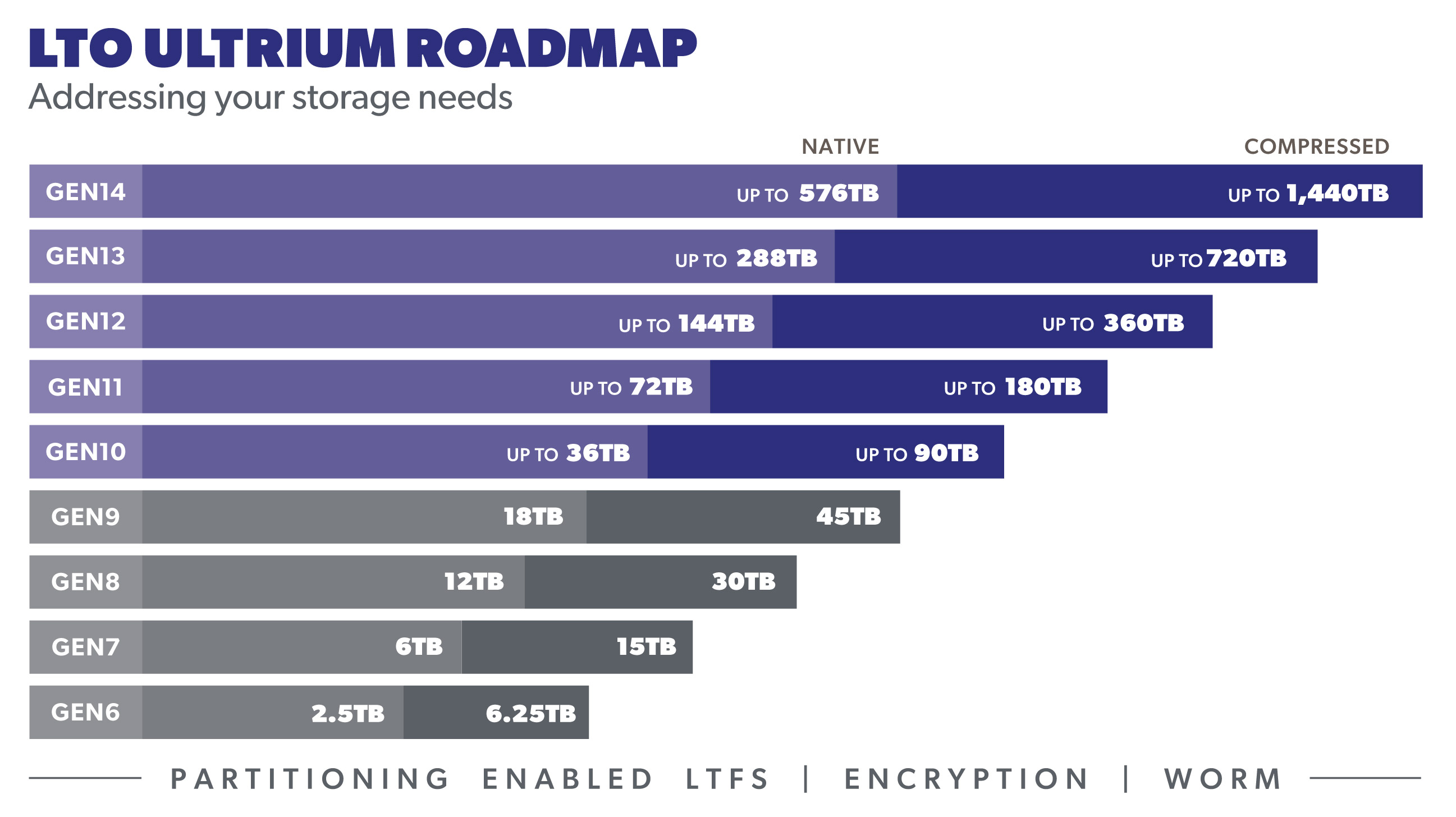

The companies behind the LTO (Linear Tape Open) standard recently published a new roadmap that extends the format up to a proposed 1440TB 14th generation. Can it deliver?

Tape still has a vital role when it comes to media storage, especially up at the enterprise level where a lot of the really expensive automated library systems are based around it rather than hard drives. It’s comparatively cheap, currently around $0.01 per gigabyte, and sales at the moment are higher than ever; 148 exabytes of total compressed tape capacity shipped in 2021

It is therefore very much a technology that is constantly evolving, which is why the three Technology Provider Companies behind the LTO program, IBM, HPE, and Quantum, published the first new roadmap for LTO tape in eight years in September. This extended it from the currently available LTO-9 and in-development LTO-10 all the way out to a proposed LTO-14 that will drop at least a decade or more from now.

It’s an ambitious plan and it’s perhaps worth backtracking a bit to 2014 and the roadmap updates then to see just how much. Back then, the cutting-edge was LTO-6 which boasted tape cartridges of 6.25 TB compressed and drives with a 210MBps transfer rate. LTO-9 and LTO-10 were then added on to the list, with LTO-9 supplying a capacity up to 45 TB and data transfer of 1000MBps. LTO-10 is expected to deliver up to 90 TB of storage.

LTO-14 goes waaaay beyond that and is expected to provide 1440 TB. And that is huge, over 1 petabyte of compressed storage; 32x the capacity of the best currently available tapes on the market.

Critically the roadmap also sees the organisation return to its doubling formula, each subsequent generation promising 2x the capacity, which crashed and burned during the move from LTO-8 to LTO-9. We wrote about that at length here, but it’s worth a quick recap of what happened.

“The expected leap from LTO-8 to LTO-9 should have resulted in 60 TB (compressed) tapes, but in September last year the LTO announced a change of plan. Not only was the next generation going to be a year late — a four year cycle instead of the standard three — but the native/compressed capacity of cartridges had been dropped to 18 TB/45 TB. The initial roadmap, last updated in 2018, had those numbers set at 24 TB/60 TB.”

Various explanations for what happened are in circulation. The LTO organisation itself maintains it was to get something to market quickly to address pandemic-fuelled demand, others point to transfer speeds (which quite conspicuously aren’t part of the public roadmap) failing to keep up with storage capacity, and the lawsuits and legal shenanigans that dogged its release probably didn’t help either. But, either way, the 1.4 PB of LTO-14 would once have been 1.92 PB if the doubling rule had been kept in place and not downgraded to a ‘mere’ 50% increase between generations 8 and 9.

Can it keep that 1.4 PB promise or will it undershoot? Reaching 1.4 PB requires each of the next five generations to increase by 100% without fail. The organisation certainly seems to think so, reckoning it is possible to increase the capacity of tape technology at historical rates through to ‘about 2030’.

“As an example illustration, recent 18TB disk product must use 1022 Gb/in2 vs the latest 18 TB LTO-9 cartridge that only uses 12 Gb/in2,” it states. “That means that LTO-9 tape can achieve the same capacity with only 1/85th of the areal density than that of same capacity disk. Simply put, tape has much more recoding area compared to disk and will be able to expand further in the years to come, according to INSIC. The combination of tape area and the ability to increase areal densities is the main reason why tape will continue to enjoy the 40% per year capacity growth.”

As to timeframe, nothing is exact. If LTO-10 ships as expected in 2023/24, then we will be hitting LT0-14 anytime between 2031 and 2036 as long as the typical two to three year cycle per generation is maintained. That, of course, stretches beyond the 2030 date mentioned above, so the chances are that at least one technological rabbit will have to be pulled out of a hat somewhere along the line to maintain the rate of progress.

Tags: Storage

Comments