Replay: Scenes involving multiple actors can throw up multiple issues when setting up lighting for both dramatic effect and shape. Neil Oseman takes us through the process and considerations of illuminating multiple actors in a dialogue scene.

In an earlier article, “The One Simple Secret of Lighting a Face”, I discussed short key, a rule of thumb for placing your main light source. Today I’ll look at how this concept can be developed for a typical scene involving two actors.

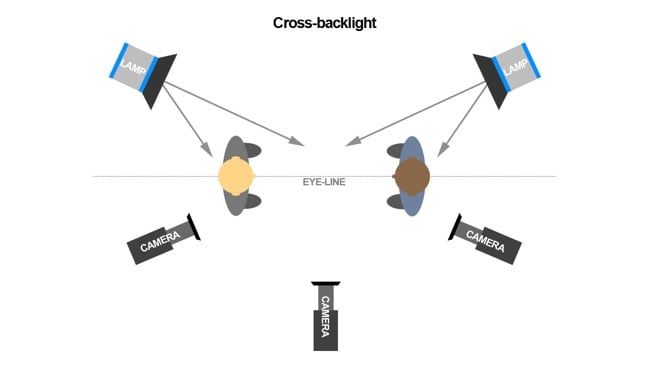

A short key, to recap, is a key-light placed on the opposite side of the actor’s eye-line to the camera. It brings out the shape of the face, putting the near side in shadow. If we have two actors, standing opposite each other and talking, for example, we can set up a short key light for each person which doubles as a backlight for the other. This is known as cross-backlighting.

The beauty of cross-backlighting is that it leaves the close side of both actors’ faces in the shadow for the best contrast and dimensionality, wherever you put the camera — assuming that you’re obeying the 180-degree rule by always staying on the same side of the eye-line. Your over-the-shoulder close-ups have a nice three-quarter short key with backlight on the same side and your wide and two-shot show light wrapping around both sides of both actors.

But we don’t necessarily need two discreet, crossed sources to create a cinematic look. The principle is to shoot towards the light and arrange it to wrap around the faces.

When we first start taking pictures or shooting video, we are often taught that we shouldn’t shoot into the light: if we’re indoors we shouldn’t shoot towards windows, if we’re outdoors we shouldn’t shoot towards the sun. This is largely because beginners use auto-exposure, which will compensate for the bright backlight by turning the subject into a silhouette. But if we’re shooting professionally, particularly if we’re aiming to shoot cinematically, then pointing the camera into the light is exactly what we want. This is because it creates a master shot that sets us up for success with all the other coverage by establishing light from behind, which will become a short key when we move the camera around to either side for the close-ups.

Imagine two people sitting opposite each other at a table in a café. Very often you will see such scenes in films and TV staged with the couple sitting in the window and the camera facing towards that window. Essentially, the light from the window (be it natural or otherwise) is cross-backlighting the cast. It’s hitting the sides of their faces away from the camera, wrapping around — the wider the window, the more the light wraps — but leaving the camera side in relative darkness.

Take another example, a nighttime interior with practical table lamps. Most DPs will always want to put the practicals in the background of the wide shot. This is not just because the lamps themselves add interest to the frame, but because the light from them (or the light motivated by them) will short key the talent in the close-ups.

Cross back light - The Gong Fu Connection - Cannon Fist Productions - DP Neil Oseman

Recently I shot a night interior in a kitchen set. The two actors sat opposite each other across a breakfast bar. Above them was a practical light fitting, but it wasn’t very powerful and being immediately between them it hit each actor squarely front-on. I decided to set up another source, motivated by this practical, but much bigger, softer and offset from the cast, on their off-camera sides. This gave me a nice wrapping light on both actors, with their shadow sides to the camera, and it looked great in the close-ups.

Cross back light set up - Above The Clouds- Third Light Films - DP Neil Oseman

Study the lighting in film and TV, particularly those very common two-hander dialogue scenes, and you’ll see how often cross-backlighting or some variation of it is used.

Title image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Tags: Production

Comments