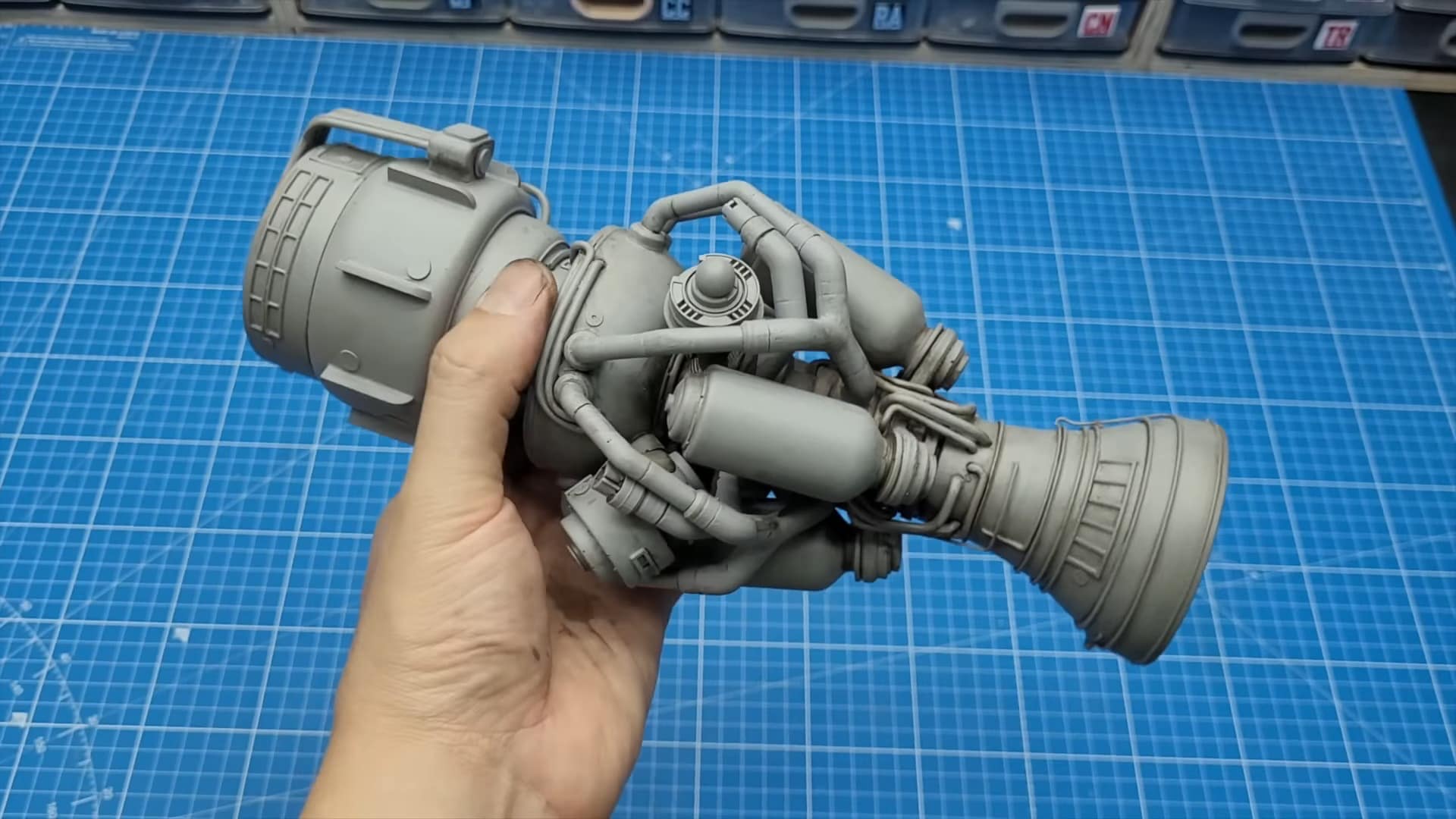

Or a spaceship cockpit in the garage or a jet engine out of an old lightbulb…Phil Rhodes on home-brew sets and effects.

There are a few reasons that historically, there’s not been many people making high-end sci-fi TV series in the back bedroom.

A lack of camera technology was the problem, but anyone who’s using that excuse in 2023 needs, in the words of the PlayStation generation, to 'git gud'. Similar things apply to advanced CGI. Ian Hubert’s one-minute tutorials don’t discuss the huge amount of preparation and editing which are required to make it look that easy, but they do make it very clear that with enough application, stupendously impressive results are possible for the cost of a half-decent workstation. We discovered as much when we talked to filmmaker George Moïse about his trailer Quest of the Gods, though we also discovered that the process was like being sent to a kind of prison where chain gangs execute visual effects shots.

What’s new is interest in original designs using the techniques which brought us Star Wars and Blade Runner and all the other movies where everything was made out of found objects. Examples abound, even at the garage-filmmaker level. People who are cautious about Blender might find inspiration in the 2019 short Slice of Life.

It’s probably all the more convincing precisely because we’re not expecting to see models in modern shorts, though the people behind Moon would probably be pleased to be the exception that proves the rule (and let’s raise a glass to the late, great Bill Pearson in recognition of his vast body of work in the field).

There’s been at least some interest in building science fiction objects for a long time. Keen viewers were creating Star Trek phasers during the broadcast of the original series in the late 60s. At least since the 80s, replica props and costumes have been more or less a mainstream hobby. This sort of thing is typified by the extremely irrepressible Svetlana from Kamui Cosplay, a galactic centre of effervescent vivacity, whose indie-friendly techniques also attract commercial clients. Modelmakers might be equally entertained by Henrique Ventura and his scratch-built modelling channel Cut Transform Glue, which more or less describes how to make camera ready models out of an antiperspirant can and old VCR parts.

It would be easy to write this stuff off as a fan pursuit if it weren’t for the British Film Institute’s sponsorship of a selection of budget how-to content on its YouTube channel. The series made reference to some of the all-time greats, particularly the famous use of scrap aircraft parts to dress the sets for Alien. The Institute doesn’t seem to have added much to that series in the last few years, perhaps in recognition that, frankly, there were already plenty of people producing very accomplished results.

The rise of the no-budget short

What it does show, though, is a degree of institutional recognition of the growing ambition of no-budget short films. The phrase “independent” covers a huge range of productions, right up to Sundance darlings which spend more on promotion than production, and there’s a big gap between that and people who’re building a space fighter cockpit in the garage using an old car seat and some string.

Original designs make things easier. Enthusiasts regularly spend hours scouring the internet for exactly the right kind of plumbing fitting to make an accurate Star Wars lightsaber, or the right burglar alarm control panel to make a shoulder lamp for a set of Aliens body armour. These things were inexpensive and common in the 80s but have spent the intervening decades accruing an enormous amount of rarity value. It’s easy to get the idea that all of these parts were chosen with exquisite skill – which possibly they were, but not with the same restrictions as we encounter when we try to recreated them today. Original designs can use parts on hand, which makes life easier.

If you’re the sort of person who likes to spend time in the shed bolting random objects together and spraying them interesting colours (and your correspondent is happy to admit to being one of those people) this is all great fun. What’s important is that it highlights is those parts of filmmaking which have been most resistant to digitisation. Sure, you can put your actors in front of an LED screen and do virtual production, but that’s the sort of approach that only saves money for productions which were already extremely expensive. Putting elaborate props into people’s hands has been done by computer, but unless that prop has some very specific requirements, it’s more trouble than it’s worth. Some things have to be built (and many more can be built).

As Doug Harlocker, prop master on Blade Runner 2049, lamented, modern high-performance production and distribution gear – read 4K TVs – means that audiences can now see the glue lines. That’s made it harder to get away with the found-parts and duct tape approach. Still, improved technology, things like like lithographic and filament-deposition 3D printing, laser cutting and other rapid-prototyping technologies, are now within reach of serious amateurs or entry-level pros.

Has all this raised the production-value bar in terms of very inexpensive short film production? Possibly. Entry-level filmmakers might well be better served by producing something set in the modern world, on real locations, as opposed to relying on wobbly-wall sets built in the garage. For anyone who’s really intent on doing that, beware the level of skill and experience required, not to mention the fact that even scrapyard set dressing may not be a complete give-away. Aliens may not have had CG, but it did have a budget. The idea that air breakers’ scrap is cheap is decidedly relative.

Either way, the positive influence of all this is in the realisation that pretty pictures begin in front of the camera, not inside it. Someone famous once said that without good production design, there is no good cinematography, and if the idea of building props, costumes and sets makes beginner filmmakers more aware of that, it’s hard to argue with.

Tags: Production

Comments