The 1980s were the decade when video began to encroach on film – certainly for TV, if not for cinema. The 1990s was the decade when digital cameras made their mark. Specifically the DV Granddaddy, the Sony VX1000.

The Sony VX1000 DV camera.

Sony’s Betacam and Betacam SP, the focus of our previous decade, were being superseded as the favoured broadcast format in the 1990s by DigiBeta. DigiBeta was an excellent SD digital component format (10-bit 4:2:2) but, in terms of cameras, it was hardly game changing. What was more interesting was what was happening at the lower end of the market.

Manufacturers had become adept at segmenting the market so they could sell at top dollar to broadcasters yet offer cheaper solutions to industrial, educational and domestic markets. At times Sony had around 20 different video tape formats on offer; even BetaSP decks were marketed at three different price levels – U, P and B – offering higher engineering standards to the broadcast markets at higher cost, but maintaining the same format spec. In 1995 a consortium of ten manufacturers introduced a new digital format that, for the first time, could be offered to both amateurs and professionals – it was DV.

The mini DV cassette, using ¼” tape and with 60 minutes recording time, was a mere 7cm x 5cm (2 ¾” x2”) , which meant cameras could be small too. For professional use, Sony produced DVCam while Panasonic came out with DVCPro. The ‘pro’ DV formats, which were not compatible with each other, offered little difference in terms of picture quality, but were more robust (wider track pitch and faster tape speed) and, in principle, more reliable for frame-accurate editing.

Sony VX1000

The first DV camcorder, Sony’s VX1000, was introduced in 1995. It looked and felt like a well-made amateur camera, but the pictures it produced were a revelation. At $3500 (equivalent in today’s money to around $5.5k)

it was a fraction of the price of Betacam cameras and offered twice the resolution of U-Matic.

The VX1000 had 3 x 1/3” CCD sensors and a resolution of 500 lines, a 10-1 optical zoom lens (20-1 with digital zoom), built-in ND, SteadyShot, zebras, auto and manual focus, built-in stereo mic and external audio inputs. Crucially, the VX1000 also had a Firewire port (which Sony called i.LINK), meaning it could be fed directly into a computer for editing. It wouldn’t be until the next decade when editing software like Apple’s Final Cut Pro arrived to take advantage of this – in 1995 non-linear editing systems relied on analogue inputs.

The author's PD150, the successor to the VX1000

At first the VX1000 was regarded as a bit of novelty, and professionals used it as a second, stand-by camera, or when they needed a camera that was small and discreet. Soon it became apparent that in some circumstances the pictures could actually look better than Betacam – the performance of analogue cameras could vary depending on how well they were maintained and the state of the heads, but the pictures coming out of the DV cameras were always sharp and clean and could be copied through several generations without noticeable deterioration. There was some embarrassment that the cassettes were so small they didn’t look ‘professional’ and I remember some crews actually only changing cassettes when the client wasn’t looking.

The VX1000 was what many observational documentary makers had been dreaming of – a small, inexpensive camera that could run for an hour on one tape that produced pictures you could broadcast. Although, in principle, the DV format has never been accepted as broadcast spec in the UK, many thousands of hours have been transmitted, either through special dispensation when a discreet camera was needed, or simply smuggled through by dubbing on to a ‘broadcast standard’ tape. In low light the VX1000 produced pictures with a gritty quality that some at the time regarded as ‘film like’. For personal, single-crewed documentaries and low-budget filmmaking in general it was a godsend.

The VX1000 was later superseded by the VX2000 with improved light sensitivity and a companion ‘pro’ version, the PD150, which added XLR inputs and independent gain and iris controls. David Lynch famously shot his acclaimed feature Inland Empire entirely on PD150 cameras.

BBC adoption

Audio quality was a weakness on the VX1000 and its successors; there could be an unacceptable hiss and, on some models, using manual audio gain resulted in more noise than leaving it on auto. The BBC took this seriously enough to make there own modifications to the VX2000, by-passing the internal electronics and routing audio through a custom made ‘Glensound’ box.

In some ways the DV formats, were better than they were supposed to be, eating into markets that should have been the preserve of higher spec broadcast cameras – particularly in the case of the larger, shoulder-mounted ½” chip DVCam cameras.

The VX2000 and the PD150 were superseded by the VX2100 and the PD170 and PD175 and then Sony’s Z series which offered 1080i HD pictures in the HDV format. But it was the VX1000 that broke through the line between professional and amateur video cameras and the tradition continues to this day with ‘prosumer’ handheld cameras marketed to both to broadcast and domestic, sometimes with slight variations (like XLR audio inputs for pros and minjacks for consumers).

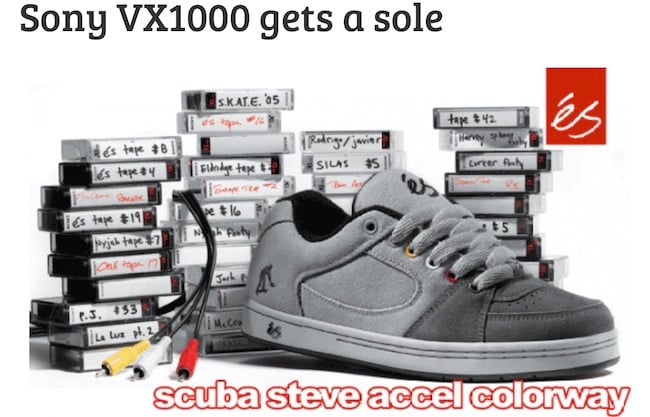

One final accolade for the VX1000 – it is the only camera I know of that actually inspired a shoe.

Tags: Production

Comments