Replay: It is hard to imagine the impact that a cumbersome, reel-to-reel black and white video recorder could have when mobile phones record 4K video, but back in the 1970s, it was a game-changer.

The Sony AV-3400 Video Rover — the ‘Portapak’ — was not the only portable video recorder around at the time, but it was by far the most successful and it spawned a whole genre of video making. Its impact was massive because, for the first time, ‘ordinary people’ could make television. Or so it seemed.

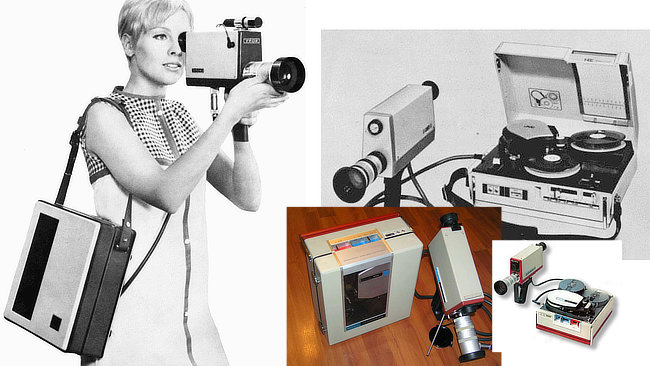

Looking at it today reveals just how far we have come. A two-piece unit — camera and battery-driven VTR — the Portapak recorded black and white video onto reel-to-reel 1/2” tape. With battery and tape, the recorder weighed 18lb, 12 oz. The 5” reel gave you about half an hour of recording time. The camera had a built-in microphone but the adventurous could re-dub the audio track on the VTR. The pictures weren’t great but they seemed good enough to just about pass as TV.

The whole unit cost around £1000 in the early 70s — equivalent to something like £12,000 in today’s prices. If that seems an astonishing amount of money, you have to realise that at the time the cheapest way to make films with sync sound was to shoot on 16mm and even a £1000 budget would only have covered for the cost of one very modest film. And the Portapak was typically bought not by individuals but organisations — arts organisations, colleges, community groups — as a shared resource, much as they might have bought a van.

The VTR unit was slung over the shoulder in a thin plastic case and tended to get knocked around, so unsurprisingly, the Portapak was not known for its reliability; tape would jam, video heads would clog and drop-outs were common. Initially, any form of editing was out of the question, but soon edit capable VTRs arrived. Editing consisted of connecting the Portapak to the editing VTR, running for a few seconds so they both got up to speed and pressing the ‘edit’ button to record from the Portapak to the VTR. If you timed your start points on both machines with a stop watch it was possible to create edits to the accuracy of about half a second. There was no timecode or any way of locking these machines to enable more accurate edits.

An exotic and expensive process

It is essential to remember that in the early 70s editing video was an exotic and expensive process. Two-inch quad tape was the broadcast video standard and TV programmes were either recorded in a multi-camera studio or shot and edited on film. The portable video camera had not yet arrived in the broadcast world. Shooting events outside on video required an Outside Broadcast Unit — a mobile TV studio in a series of vans. The fact that the Portapak was some sort of portable TV unit seemed a miracle in and of itself.

And what did people do with it? Given the cost and the clumsiness of the equipment, it was amazing that anything was shot at all, but it became a hugely important resource. Perhaps the most significant development to come out of the Portapak was ‘community video’. Groups up and down the country helped communities make videos about their housing conditions, their work environments, their strikes. Schools filmed their theatre shows, youth clubs enabled kids to make their own crude TV programmes. Artists, although more drawn to 16mm film as a medium, used the Portapak to record performances and began to explore its limited technical possibilities (often by pointing the camera at the monitor and experiencing video feedback for the first time).

By the mid-70s non-profit organisations like Fantasy Factory and London Video Arts (later London Video Access) were offering editing suites and camera kits to community groups, artists and those who saw themselves as part of an underground/alternative movement. In 1976 I borrowed the only Portapak in London with a low-light capable camera to record the burgeoning punk music scene.

By the end of the 70s 1/2” black and white tape and the Portapak had been rendered obsolete by Sony’s U-Matic system. This recorded onto 3/4” cassettes in colour. Most importantly, two U-Matic decks could be linked together by an edit-controller enabling reliable, cuts-only editing. With a three-machine suite, you could even mix images. In the 80s Sony introduced their broadcast version of U-Matic (BVU) and portable VHS and Betamax units made video cameras and recorders affordable to individuals for the first time.

The pioneering days of the Portapak and the people’s TV revolution might now seem slightly quaint, but maybe there is something we can learn from it. The excitement of working with a new medium and commitment to push it as far as it goes can take you way beyond the technical limitations of the equipment.

Tags: Production

Comments