Is Instagram the future of video?

Is Instagram the future of video?

What does quality mean these days? There is almost no limit to the quality of video we can capture now, and yet, low-fi and Instagram are increasingly popular. What's going on?

Do you remember HiFi? There was a time when it was positively fashionable to buy the very best stereo system you could afford, and it was a mark of career success and affluence if you could afford to buy a really expensive stylus for your record player.

All of this started to change when digital audio arrived in the living room in the form of the Compact Disk in the early 80s. "Perfect sound forever" said the optimistic, not to say misleading advertising copy.

Misleading?

Yes. The sound wasn't perfect. And the disks don't last forever. But it did make a very good point. While the sound wasn't perfect, it was digital. And that meant that it wasn't going to be affected by dust, scratches and fingermarks on a vinyl record. It also meant that to hear your precious records, you didn't have to drag a needle through a wobbly groove. With CDs, there's no contact.

Once we got used to the idea that if CDs weren't perfect, they were capable of sounding very good, and the HiFi race carried on. There was no limit to what you could spend on CD players with esoteric power supplies, and for those with more money than sense, or simply none at all, "Bit processors" that cost $22,000 dollars without actually making the sound discernibly different.

Paying more for high-end Digital to Analogue converters was probably a good thing, although you quickly get to the point where the room acoustics have more influence on the sound of your system than the egregiously expensive tube pre-amp that you bought instead of a motor yacht.

Meanwhile, most of us were happy to buy a small CD stereo system from the likes of Aiwa with a built in cassette deck that helped us in the transition from analogue to digital.

Napster, MP3 and the iPod

And then came Napster, MP3 files and, finally, the iPod. In retrospect, Sony probably privately wishes that it had supported MP3 from the start, because the fact that its early digital Walkmans didn't support MP3 proved to be a serious flaw in their strategy when people realised that if they bought Sony they just couldn't take part in the file-sharing revolution.

The elephant in the room alongside all of this is that as music separated itself from physical media and jumped into the IT domain, the compression meant that not only did the actual quality diminish, but people's expectations of quality took a dive as well. There's no reason why even CD quality shouldn't be vastly exceeded with more modern formats - and it has been in some cases, but the fact that these better and purer ways to store and reproduce audio haven't taken off in the mass market suggests that quality is not a major factor for most people.

In fact, it's become a perfectly accepted part of modern music production to degrade audio with distortion, bit-crushing and even simulation of vinyl recording. These various ways to degrade an audio signal seem are treated as a creative effect, along with traditional reverb, EQ and (dynamic range) compression.

And almost everything to do with the familiar sound of an electric guitar is achieved through adding distortion.

Is mangled content better?

In a strange sort of way, we prefer our content to be mangled. Of course, there are some methods that don't look good, but you can't escape the fact that much of what we hear or see has been degraded in some way for a creative effect.

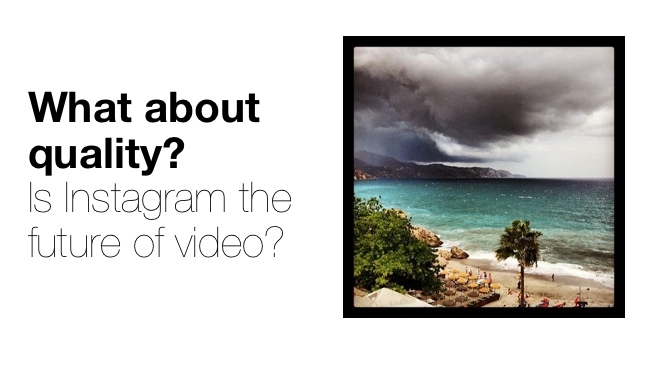

Just look at Instagram. You can choose various "looks" to apply to your photos, and they almost invariably make your pictures look better - sometimes stunningly so! There's a debate in pro photography circles about whether it's ethical to use Instagram in serious photo work. I think it probably is OK, and of course, there's no parallel discussion in movies because with raw footage (and most other footage as well) you absolutely have to choose a "look" for your production.

Distortion can help in other ways as well. The early attempts at CGI-based dinosaur documentaries suffered not only from relatively low-polygon models, but also from the difficulty of blending CGI footage with real backgrounds. It's very much easier now, because you can add camera shake, motion tracking and depth cues like distance fogging that trick us into thinking the CGI element is real.

In fact, distortion is part of real life. It's how we see life itself. We don't have pixels in our retinas. We don't suffer from "camera shake" in our eyes when we jump or run. Our reality is made from disparate elements that we perceive. We cope with bad eyesight. Only the very central part of our vision is detailed. The only way we can see the wider world around us is by rapid eye movements that we're barely aware of - and our cognitive system pieces together an impression of a contiguous whole world out there.

Do we want the purity of modern cameras?

Modern cameras can bring us a purer view of the world. But purity isn't necessarily what we're craving. What we want is an engaging world that pulls us in, that intrigues us, and that pleases us. Grey days and dark, dimly lit nights aren't enough for us. We need sweeteners and seasoning.

More pixels and bigger dynamic range help us to create our fantasy world by giving us the space in which to apply our imagination (and, yes, our mutilations to the original images). Nobody complained that an oil painter had his or her colour balance wrong (or someone, surely, would have had a word with Rembrandt). It's the reduction in quality, and the way it's done that separates art from reality.

What's more, somewhat ironically, the more resolution we have available to us, the more we can capture and reproduce the visual nuances of lenses that have imperfections. Every little subtlety and defect will become part of the look of the film itself.

But isn't this sacrilege? Isn't it perverse and anti-art? What's the point of developing camcorders that capture higher resolution moving images than some still cameras?

Power of choice

That point is that directors and DOPs now have a choice. They can go for a pure, transparent look on the set, or they can deliberately modify the look with a specific lens. Either way, with the stratospheric quality available to us now, there's so much more we can do in post. And if we want to, we can be much more extreme.

For people that need to make videos - documentaries, news, interviews; all the usual stuff, life will go on and their pictures will get better. For those making Video As Art, the possibilities are now wider than ever. It's good to take risks. Making the film Gravity was a huge risk and entirely dependent on technology. But now you can experiment with low budgets to see if your CGI masterwork is going to be feasible. With cameras and software tens if not hundreds of times cheaper than before, you don't need to look over your shoulder now before you "mutilate" your footage, and present it as an example of your creativity. And this is a good thing. It's how you push boundaries and how new art forms are created.

Tags: Post & VFX

Comments